Growing like a weed

As more states unwind their restrictions on cannabis, businesses find opportunities and challenges in an emerging industry

By Matthew Biddle

Back in 2014, Daniel Humiston, CEL ’93, was already a successful entrepreneur. He had started and sold a software company, and owned a chain of tanning salons with more than 500 employees. He was once named Entrepreneur of the Year by EY, and even ran for Congress.

Humiston

Outside of work, Humiston was a triathlete who didn’t smoke or drink alcohol. So, people were more than a little surprised when he told them he was moving into a new industry—cannabis.

“I had been in a bad bicycle crash and had to lie in my bed for four months,” he recalls. “I was stressed because the tanning industry on the decline, and saw a ‘60 Minutes’ episode about this opportunity.”

Washington and Colorado became the first states to legalize recreational cannabis in 2012, and by the end of 2013, 19 states and Washington, D.C., had legalized it for medical use. New York approved its medical program the following year.

But public opinion was mixed, at best. When Gallup first conducted a poll on cannabis legalization in 1969, only 12% supported it. More than 40 years later, support for widespread legalization finally cracked 50%—but that belied significant gaps in sentiment based on geography, politics, age and religious attendance.

Still, Humiston saw business opportunities in an emerging industry. In 2014, he launched the Cannabis World Congress & Business Expo with events in Las Vegas and New York. Now, he also is CEO of podCONX, a series of cannabis-related podcasts on everything from women in the industry to medical marvels to job opportunities.

“When I first started, I was also a ski instructor, and a lot of parents questioned whether they felt comfortable with me as their kid’s coach,” he says. “There was a general feeling among my friends and family, like, ‘Wait a minute—this is crazy.’ Fast forward eight years and the same people who looked at me sideways are like, ‘How can I get into this? Where should I invest or buy stock?’”

Today, with regulations loosening in many states, public opinion on cannabis continues to shift, encouraging additional states to relax their laws too. This year, Alabama became the 36th state to allow medical marijuana, and New York, Virginia, New Mexico and Connecticut brought the number of recreational cannabis states to 18. In turn, a recent Pew Research survey found 91% of Americans say cannabis should be legal—60% said for medical and recreational use, and another 31% for medical use only.

All of this activity has allowed a new industry to take root. Legal sales hit a record $17.5 billion in 2020, according to BDSA, a cannabis sales data platform. By 2026, BDSA projects the legal U.S. market will hit $41 billion in sales, roughly the size of today’s craft beer industry. For entrepreneurs and other professionals, this could represent a big opportunity—if they’re willing to take an even bigger risk.

Pharm to table

Williams. Photo: Tom Wolf

Lee Williams, JD/MBA ’16, serves as general counsel and director of business development for Dent Neurologic Institute, the largest outpatient neurology practice in the U.S. Among other roles, she ensures the organization complies with all legal standards, including New York’s medical marijuana program. Dent has certified more than 12,500 patients to use medical cannabis, along with another 5,000 patients for CBD, a component of cannabis or hemp. (The latter is a strain of the cannabis plant with less than 0.3% THC, the compound that produces a “high.”)

If you’re confused about the difference between these plants and products, you’re not alone. That’s why when Williams co-taught a winter semester course for the UB School of Law on the legal issues in cannabis, she started with some history and definitions.

Research, her lecture noted, suggests marijuana may be the longest cultivated plant in the world—a “cash crop before cash.” In the U.S., the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 placed the first federal restrictions on it, and by 1937, it was banned nationwide. In 1971, cannabis was classified as a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Substances Act, putting it in the same league as heroin and ecstasy—where it remains today.

“We’re essentially operating in that gray area where the state allows it, but the federal government does not,” Williams says. “Cannabis currently is not part of the Justice Department’s enforcement objectives, but there’s always that risk.”

Williams says cannabis has been effective for patients with chronic seizures, Parkinson’s, post-traumatic stress disorder and neuropathy, along with migraines and other chronic pain, which represent about three-quarters of Dent’s cannabis patients. But its federal status prevents researchers from conducting clinical trials and other forward-looking studies to demonstrate its efficacy on a large scale.

“Our job is to make sure patients with severe neurological disorders have access to every therapy out there,” Williams says. “We’re a huge research institute with 100 studies going on at any time—and none of them are prospective research on cannabis. That’s a failing at the national level that is crippling the science.”

Zielinski

So far, the Food and Drug Administration has approved just one drug derived from marijuana to treat epilepsy. And, Larry Zielinski, executive in residence for health care administration in the School of Management, is skeptical that more are coming down the pike, given estimates that put the cost of bringing a single drug to market at $2.5 billion.

“In many places, this drug will already be readily available through legal recreational means at affordable prices,” Zielinski says, noting that health insurers don’t cover cannabis, and some doctors are hesitant to recommend it without peer-reviewed research. “There is no business model to support expensive clinical trials.”

The green rush

The discrepancy between federal and state law creates significant obstacles—and confusion—for businesses and individuals. Veljko Fotak, associate professor of finance, notes that immigrants investing in a cannabis business could face deportation for violating federal immigration law. In June, when Amazon announced it would no longer test job applicants for marijuana, it captured headlines—since federal labor law means employers can still fire you for smoking during off hours. Pot is prohibited in federally assisted housing and at higher education institutions that receive federal funding, including UB.

Many businesses face issues when securing a lease, getting insurance and, especially, in both obtaining capital and keeping it away from Uncle Sam.

After 200 episodes of his podcast, “Raising Cannabis Capital,” Humiston knows this story well: Fearful of crossing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and Federal Reserve Bank, most major financial institutions will not issue loans, open accounts or process credit card payments for cannabis businesses. In turn, some companies are forced to accept high-interest loans from small or niche lenders.

“A good chunk of people in the industry are still bootstrapping it, living sale to sale or borrowing money from family until they get traction,” Humiston says. “A lot of business is still in cash, which is scary. You don’t realize how challenging managing cash is until you have hundreds of thousands of dollars and can’t write a check.”

Fotak

The SAFE Banking Act, which passed the House with bipartisan support in April, would change everything, preventing regulators from going after banks for cannabis-related services. But, while the bill awaits action in the Senate, businesses are getting creative. For example, Fotak has seen two companies operate in the same space, one selling cannabis, the other selling related merchandise. The non-marijuana business then covers rent and other expenses—and may even “buy” its inventory from the other side—to reduce costs and bring in cash for the cannabis business.

“Truth is, capital flows—when you put up barriers, capital finds a way around them,” Fotak says. “But barriers create friction—and friction, in this context, leads to a higher cost of capital—which ultimately means fewer stores, fewer jobs and a persistence of black market sales as legal cannabis is priced out of the market.”

On the taxation front, businesses—and customers—must contend with different rules at the federal, state and local levels. In Alaska, while sales aren’t subject to a statewide cannabis tax, municipalities may tack on a small excise tax. Meanwhile, Californians are taxed anywhere from 23%-38%, including a statewide cannabis excise tax, sales tax and local taxes.

Salzman

At the federal level, explains Martha Salzman, clinical assistant professor of accounting and law, Section 280E of the Internal Revenue Code dictates that companies “trafficking in controlled substances” cannot deduct operating expenses for tax purposes.

“That makes doing business in this industry different than most every other kind of business,” Salzman says. “While they can reduce their gross receipts by the cost of goods sold—inventory for a dispensary, or raw materials and production expenses for a farm—for federal income tax purposes, they cannot deduct advertising, selling and other business expenses. The impact of that could be substantial.”

High hopes

Hughes

Cannabis retail sales will begin in New York in 2022, and businesses are gearing up to get a slice of what’s projected to be a $4.2 billion market by 2027, according to MPG Consulting. Thomas Hughes, BS ’10, senior associate and co-leader of the cannabis practice at Lippes Mathias, says there may be up to 1,000 retail licenses in the state, and he’s already helping clients prepare for the application process.

“The startup costs can be significant, but at the end of the day, there’s a huge untapped market here,” he says. “We’ve seen it in other states; if you have the right business plan, there is money to be made in retail, cultivation, processing and distribution. I expect there are going to be a lot of cannabis-related millionaires in Buffalo.”

Many investors are certainly optimistic, Fotak says.

“Over most periods, ‘sin’ stocks tend to outperform the market,” he says. “The simple fact that some investors, for moral reasons or internal constraints, will not invest in these businesses means the price of a ‘sin’ asset tends to be undervalued and produce abnormally high returns.

“But these high returns come with high risk,” Fotak emphasizes. “As with any nascent industry, it will consolidate—the winners will profit enormously, but many businesses will die along the way.”

Perhaps the best investment, Fotak suggests, is not in the plant-touching operations, but in suppliers and other services instead—the old cliché of selling shovels in a gold rush. After all, as Humiston points out: A cannabis business needs the same things every other business does, representing opportunities for firms in quality control, recruiting, packaging, tech and other sectors willing to jump in.

“It’s like there’s this moat around the cannabis industry,” he says. “Because it’s still federally illegal, these ancillary services aren’t competing against the big guys. That’s where most of the money is right now.”

The question now is what happens when that moat fills in, especially if the federal government reschedules or decriminalizes it altogether. History is rife with examples of mom-and-pop shops being overtaken by corporations as industries matured—is that the future of cannabis?

At least in New York, Hughes says the Marijuana Regulation and Taxation Act has provisions reserving microbusiness licenses and giving priority to certain demographics to promote social equity and economic opportunity.

“The legislation has a huge social equity component that’s intended to open up the industry to a broader extent than other jurisdictions have,” Hughes says. “But there will also be issues for smaller businesses in creating economies of scale or tracking the product—your supply chain has to be flawless. It’s a unique experiment that could fall flat or succeed in reducing barriers for a much larger demographic to participate in the cannabis industry.”

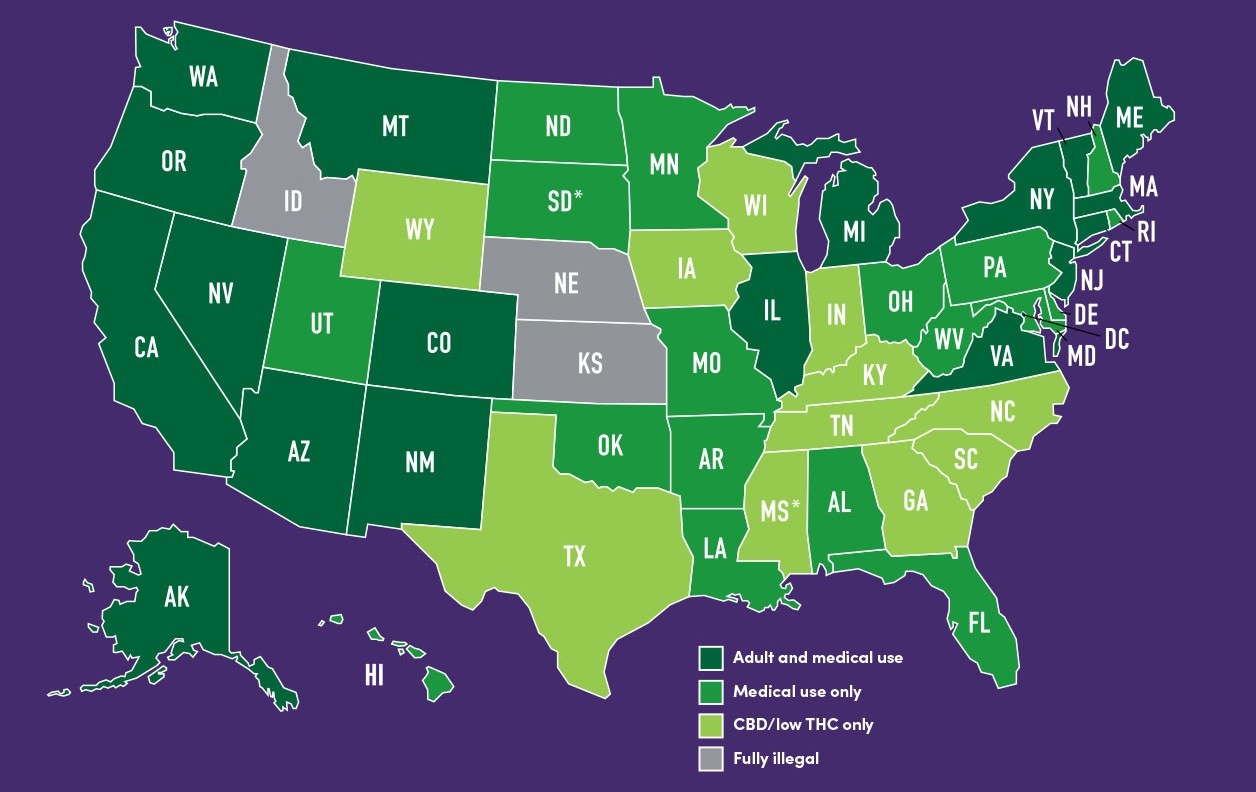

State of the Union

While cannabis remains illegal at the federal level, laws are changing fast in states across the country, either through ballot measures or the traditional legislative process. At press time, here’s where each state stood.

* During the 2020 election, voters approved ballot initiatives allowing adult use in South Dakota and medical use in Mississippi, but both were overturned by state courts in 2021.

Source: National Conference of State Legislatures, July 2021

A ‘Growth’ Market

For further evidence of movement in the marijuana space, look no further than Canopy Growth, a cannabis consumer product company that counts Martha Stewart among its strategic advisors.

“The cannabis industry has changed dramatically over the past three years, largely driven by the opening of Canada’s recreational market and momentum at the state and federal levels in the U.S.,” says David Klein, MBA ’89, CEO of Canopy Growth.

Klein

Klein previously served as CFO of Constellation Brands—a Fortune 500 producer of beer, wine and spirits—and was instrumental in the corporation acquiring a stake in Canopy. Under Klein’s leadership, Canopy is capitalizing on Constellation’s insights and distribution power to take advantage of gaps in the market. The Ontario-based company is traded on the Nasdaq and Toronto Stock Exchange, and has 70 retail locations across Canada under its Tweed and Tokyo Smoke banners, which allow the company to test innovations before bringing them stateside.

“We have an incredible opportunity to transform the way people see cannabis,” he says. “A great example is our beverage strategy, where consumers are looking for ways to experience cannabis that are familiar and convenient. Whether that’s replacing an evening glass of wine with a cannabis beverage, or having a CBD beverage instead of an afternoon coffee, we offer products perfectly suited to introduce consumers to the category.”

Despite its growth, Klein says the industry is still in its infancy—and Canopy will keep pushing upward.

“We’re early in the evolution of the cannabis and CBD markets,” he says. “If we’re trying to climb to the top of Everest, we’ve arrived at base camp. But through our commitment to innovation and positioning for the opening of the U.S. market, we’re advancing towards the summit.”