Breaking the chains

Why supply chains have crumbled—and what’s ahead

By Kevin Manne

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, shoppers were regularly greeted with barren shelves as stores struggled to keep up with an unexpected surge of demand for products like toilet paper, cleaning supplies and food staples.

Simpson

Eventually these products returned to local stores as demand waned and supply caught up. But other areas of the supply chain continued to struggle.

In the automotive industry, a global shortage of microchips created gridlock on the assembly line as manufacturers waited for chips to finish building cars. Consumer electronics like computers, video game consoles and smartphones were also hard hit.

Natalie Simpson, associate professor and chair of operations management and strategy, says these issues are the result of an efficiency-focused supply chain developed over the past two decades. During that time, companies continued to source lower cost goods from greater distances—a higher profit, but somewhat riskier, way to provide us with merchandise.

“When COVID arrived, it caused a drop in overseas production and shipping, followed by a catch-up surge in orders for the same goods,” says Simpson. “This surge jammed the system, because our supply chains only work when shipping is normal and steady. COVID was like a puff of air that knocked down a house of cards: The puff is the reason the cards fell, but it wasn’t the reason the structure was so shaky in the first place.”

Suresh

Nallan Suresh, UB Distinguished Professor of operations management and strategy, says supply chain problems crept up following disaster events of the early 2000s like Hurricane Katrina, and increased dramatically during the U.S.-China trade war before the pandemic.

“A lot of tariffs were imposed on goods produced outside the U.S. during the trade war, so companies began stockpiling inventory and scrambling to find new supply sources,” he says. “And then, just as industries were getting into their new normal, COVID hit and consumers began panic-buying and hoarding—all while manufacturers faced production constraints like socially distancing their workers and regularly testing them for the virus.”

Holiday holdup

As the 2021 holiday season ramped up, consumers saw shortages of toys, clothes and appliances, as well as delays in order fulfillment—all caused by global supply chain disruptions.

On Black Friday, in-store traffic was up more than 47% over 2020 according to CNBC, but was still down 28% compared to pre-pandemic levels. Online Black Friday shopping was down for the first time ever, with sales reaching just $8.9 billion for the day, compared to $9 billion in 2020.

It’s a sign that shoppers were heeding the call to shop early and avoid disappointment, says Suresh.

“We always used to say ‘shop early to avoid the Christmas rush,’ but this year it was even more important,” he says.

Wei

Mike Wei, assistant professor of operations management and strategy, says because shoppers, retailers and shipping carriers were prepared, the supply chain performed well this holiday season.

“Since we expected delays and shortages, retailers planned ahead by building enough storage and capacity and ordering extra safety stock, and consumers shopped early and local to evenly spread out the demand—both of which significantly reduced shopping congestion,” he says.

“At my house we created handmade gifts for each other, but my daughter did buy a few presents for friends three weeks before Christmas and all those orders arrived in time.”

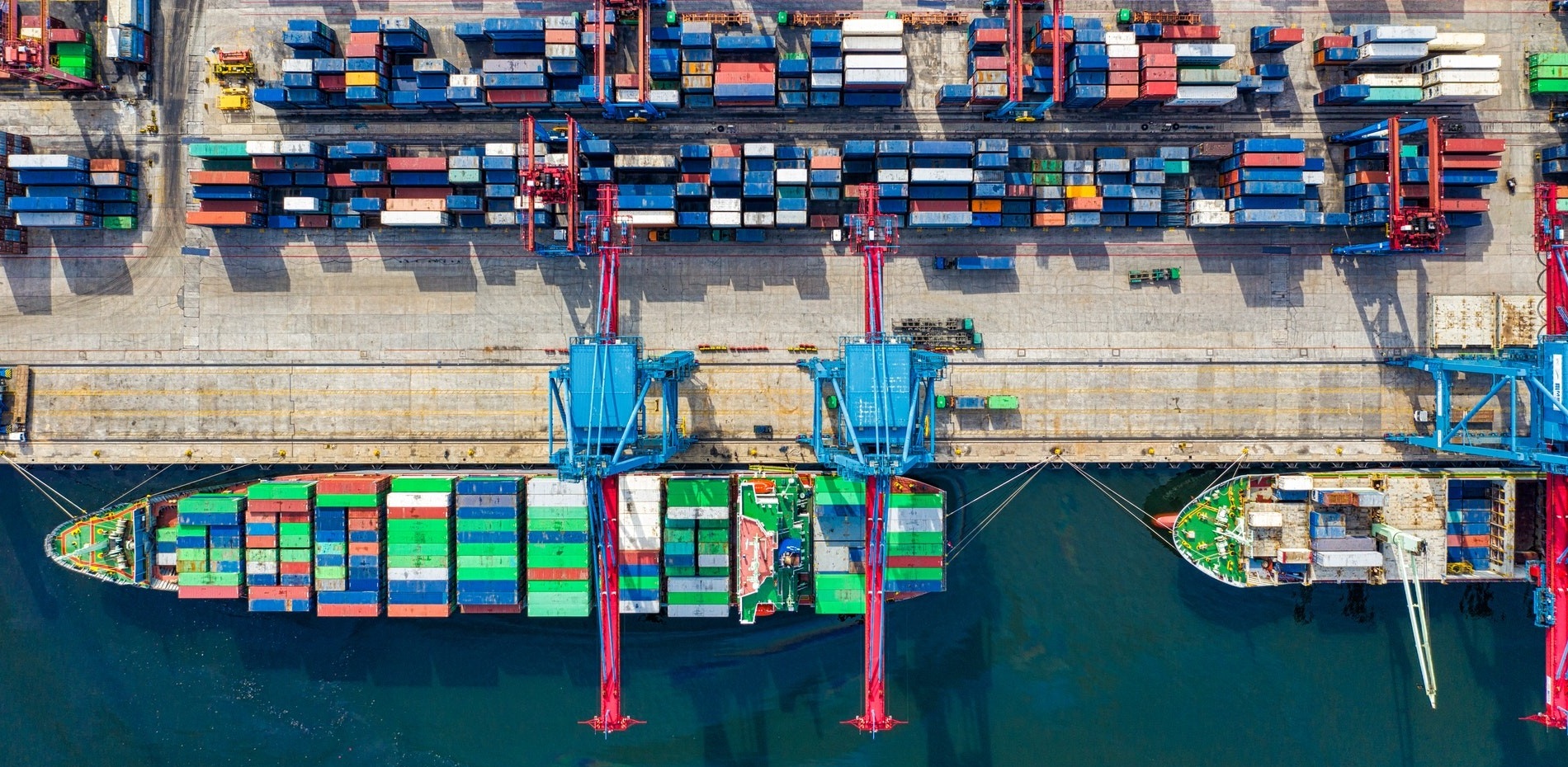

The problem at the ports

One of the most visible supply chain breakdowns was at U.S. shipping ports. And while much of the focus has been on West Coast ports in Los Angeles and Long Beach, Suresh says the issue originated more than 6,000 miles away.

“The port-related problems began in China, as the Delta variant of the coronavirus slowed operations at the source,” he says. “In addition, a coal crisis caused a power shortage for industrial use, curtailing production volume there.”

Suresh says that once all those ships do arrive, the LA and Long Beach ports become two huge bottlenecks due to shortages of warehouse workers and warehousing space around the ports—not to mention the lack of domestic truck drivers and a shortage of shipping containers.

“The bottlenecks keep shifting, so we’re going to be preoccupied with attending to one or the other for some time.”

Simpson says COVID has only amplified a problem that has long-existed at these ports.

“Congestion was already considered a long-standing problem when labor disputes at our West Coast ports disrupted holiday shopping in 2014,” she says.

Less lean?

Just-in-time or “lean” manufacturing, popularized by Toyota in the ’70s, involves ordering just enough components at just the right time for production.

The process reduces costs of excess inventory and storage while raising profits—ideal when there aren’t disruptions on the supply or demand sides. But given the impact of climate change and the pandemic, Wei says manufacturers should consider carrying safety stock to keep production consistent.

“It will be costly, but it’s the responsible way to plan your production and is the right way to handle these kinds of severe events.”

On the other hand, Simpson says only the companies that have lost money will take action.

“Unfortunately, most companies are not losing money because they are able to increase their prices and pass losses to the consumer,” she says. “We can’t expect these companies to operate any differently in the future, as the current crisis does not ultimately hurt their bottom line.”